Repair Xenteq PPI1000-212C

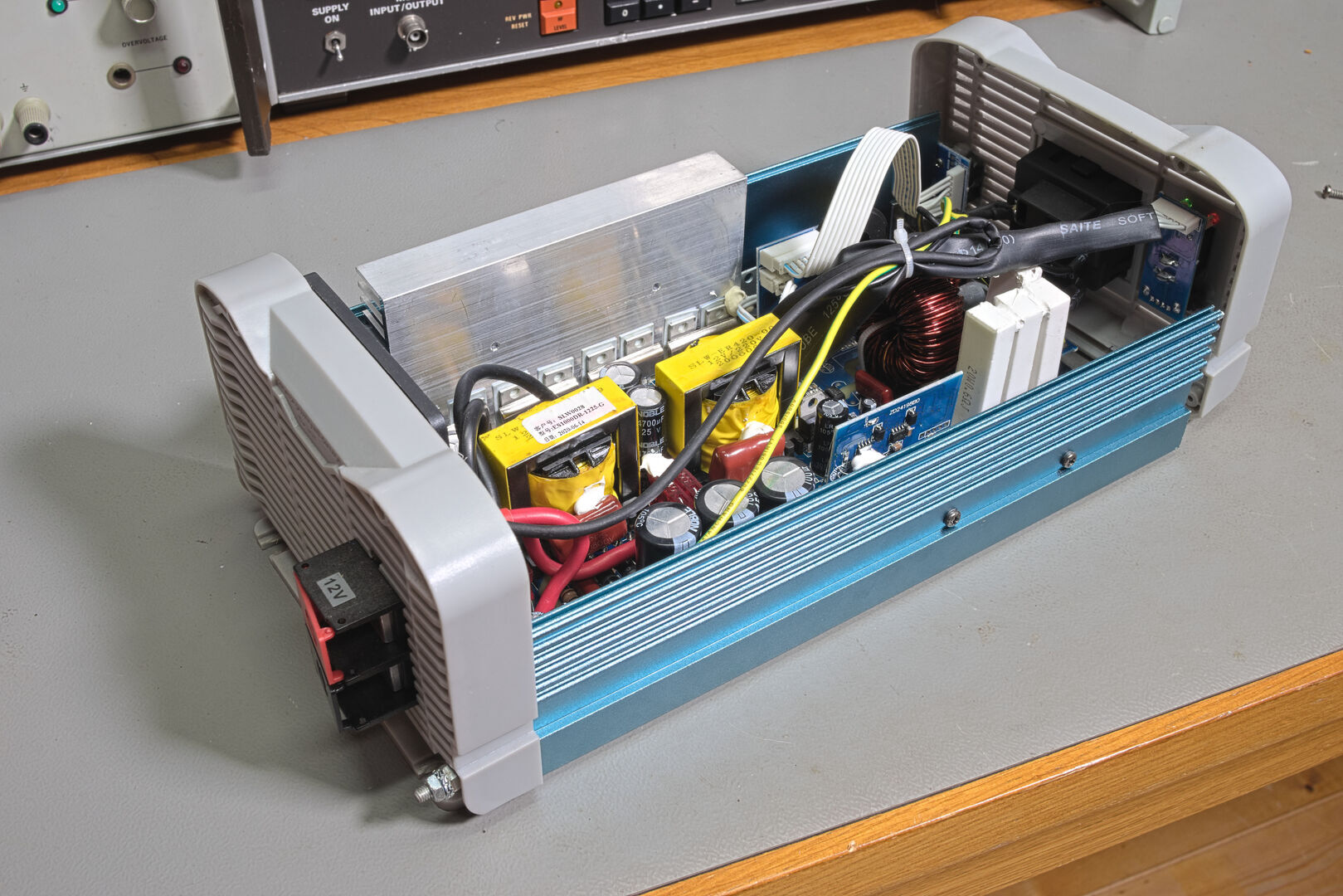

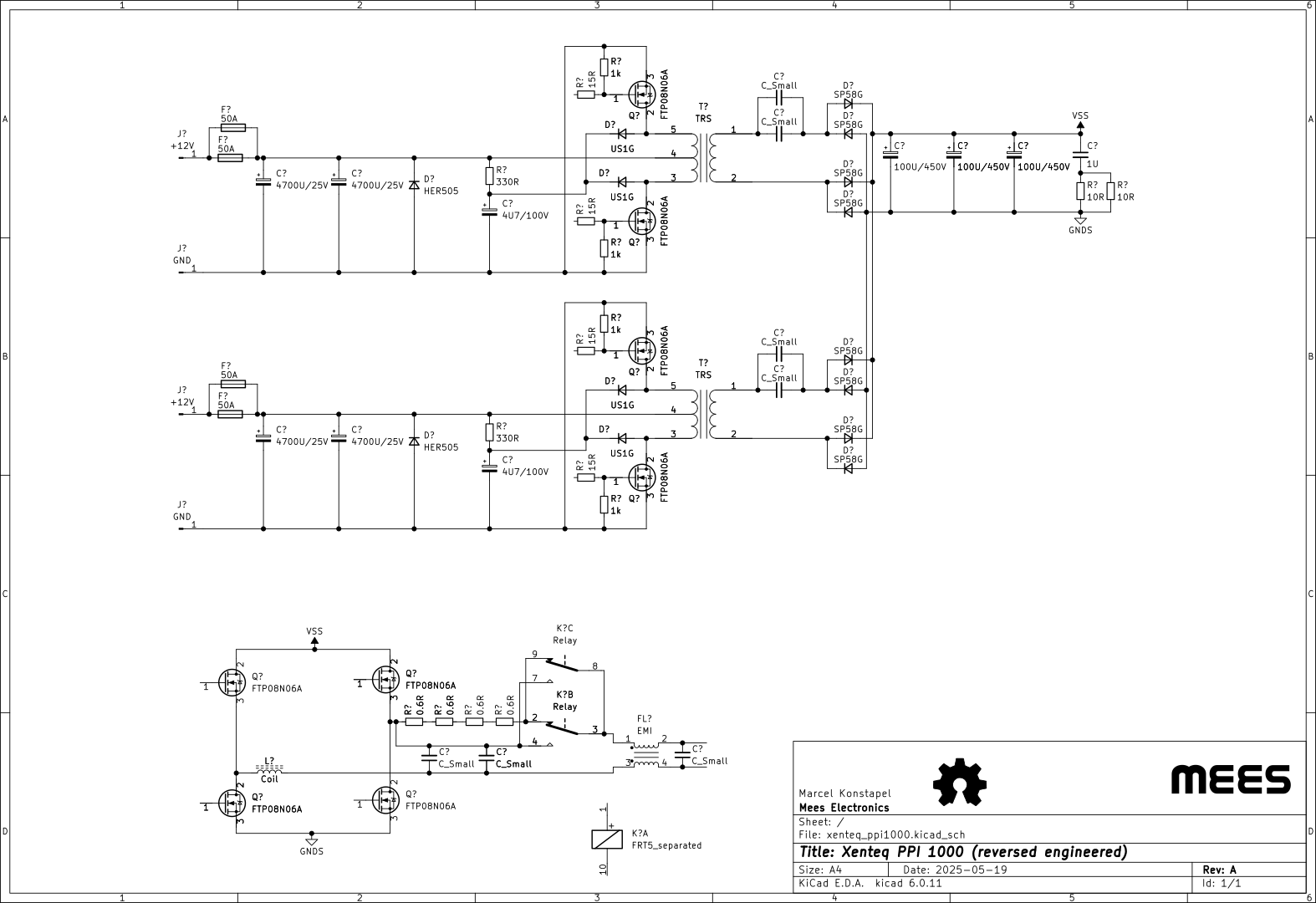

This Xenteq PPI 1000-212C sine wave inverter stopped working after 3.5 years of service. I tried to repair it, but the gate drivers were blown beyond recognition. As I could not read the part number I called the manufacturer, asking for the schematics, or at least some help. And you already know their answer, right? Indeed, a firm NO. And because the manufacturer removed part numbers from the most important chips as well, reverse engineering was almost impossible. This is a very nice example of how things have gone terribly wrong in the industry. My perfectly repairable inverter has now become e-waste, just because of the manufacturers’ attitude.

2025-05-22

The problem

The inverter just stopped working.

The theory

Ants had taken residence inside the inverter. Because ants are largely made from water, they interfered with the electrons, blowing up the mosfets.

The repair

Two of the eight mosfets of the DC/DC converter were blown. These are Chinese mosfets (FTP08N06A) and are not readily available in the Netherlands. At least not from a reputable source. But an IRF1405Z will work equally well, as it has almost the same specifications.

Two of the four mosfets of the H-bridge were blown. These are also Chinese mosfets (FSW25N50A) and are again not readily available in the Netherlands. An IRFP22N50A will work equally well, as it has almost the same specifications. The only real difference is that it can only handle 22 A of current instead of 25 A. But in this application that should not be an issue.

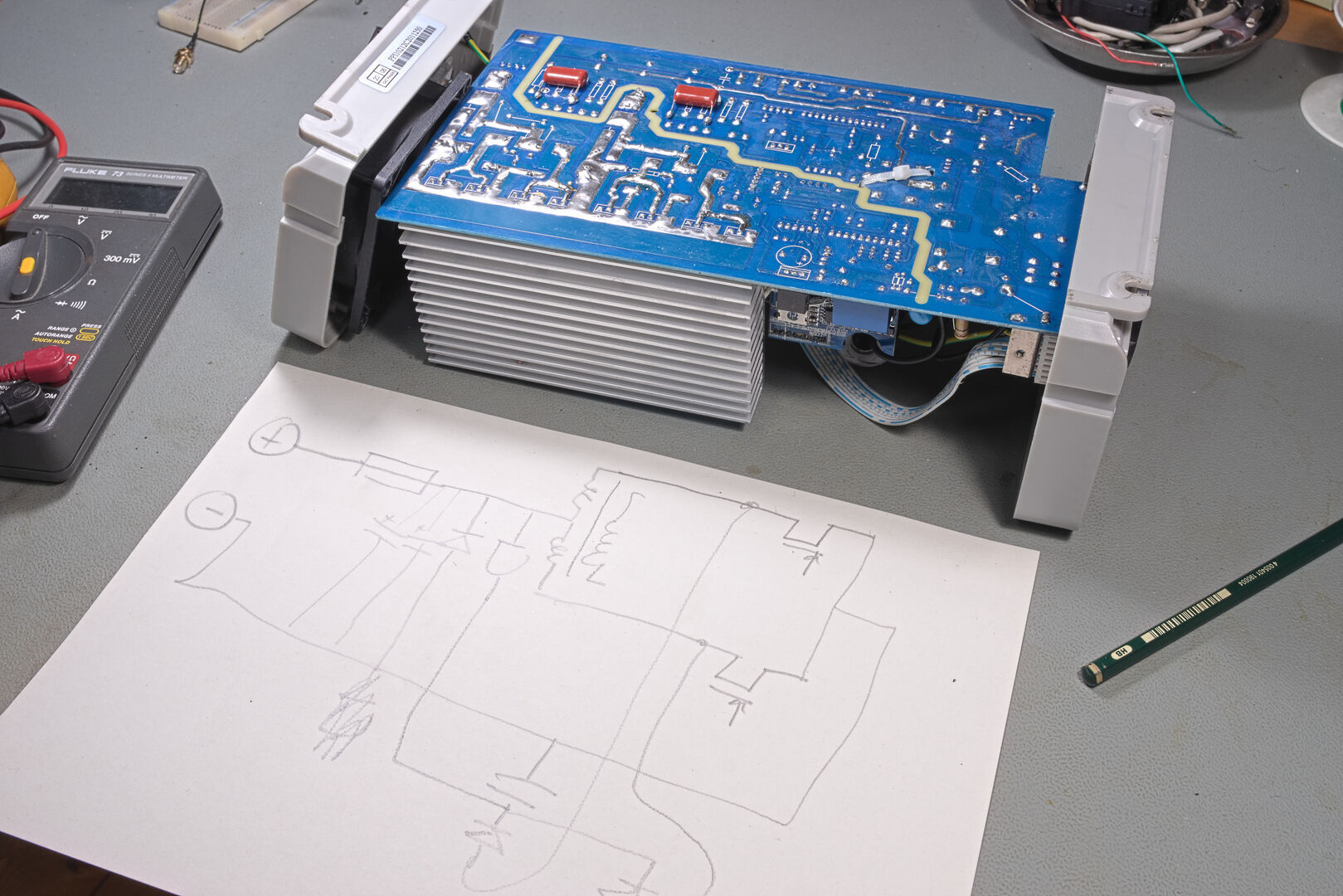

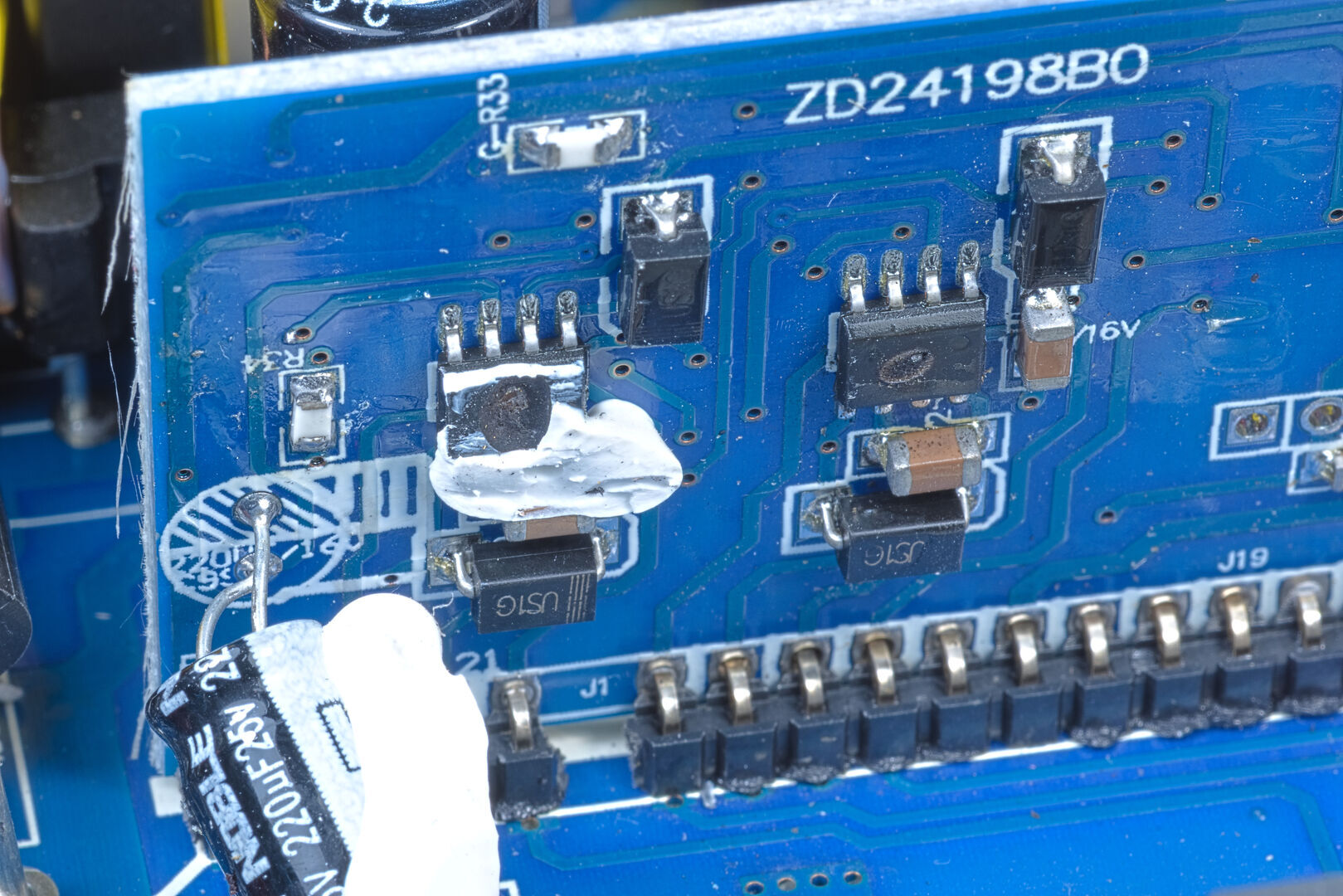

After replacing all the bad mosfets I connected the inverter to a lab power supply, so I could limit the voltage and current in case the inverter was still not working. And despite these precautions, the magic smoke still escaped. The gate drivers were also toast. I should have checked them before powering up the device, as these drivers are often damaged when the power mosfets are blown. But I forgot. And now the tops of both driver chips were damaged beyond recognition.

As I could not read the part number any more, I contacted the manufacturer, asking for the schematics. They of course said no, protecting them against evil competitors trying to steal there valuable IP. To there credit, they offer a repair service (which I couldn’t make use of, because I already had tinkered with the device). But I already started my repair and I could have easily finished it, if it weren’t for there protective attitude. Well, protective towards there money, not protective towards the environment, unfortunately.

What’s wrong with manufacturers?

In the 60s and 70s, manufacturers were proud of their products. They published comprehensive service manuals with block diagrams, calibration procedures, troubleshooting guides, technical descriptions of the workings, bill of materials and schematics. Nowadays all you get is a small booklet with warnings about what not to do with the equipment and detailed instructions of how to dispose of the device. When it is broken, you buy a new one. Which is, of course, a win-win situation: the manufacturer gets more money and the customer can buy something shiny and new. Nice!